What I Learned from Playing LoneWolf League Season #37

Reflections from an International Master's debutFrom late May through mid-August I played the Lichess LoneWolf league. This is an 11-round individual competition with Swiss-style pairings played at a pace of one 30+30 game per week. I’ve referred many students and viewers of my YouTube channel to this league and its “sister league” (Lichess 45+45) in the past, so I figured it was time to actually participate myself! To up the ante, I decided to not only record live commentary and post-game analysis for each game, but also to record and post my pre-game prep too (usually 15-25 minutes, conducted right before each game).

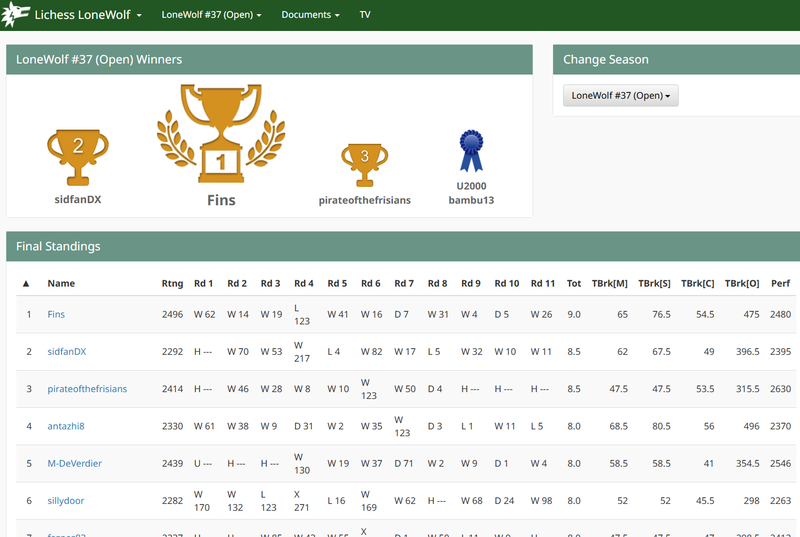

After 2.5 months of battle in a 278 player field, the results were:

- 29 hours of video

- 11 tense, full-blooded fights

- An abundance of metagame intrigue - especially in the opening

- Countless practical and philosophical lessons

- Memorable connections with my opponents and other league participants

- Some of the best feedback I’ve EVER received for a YouTube series!

In this post, I’m going to describe six things I learned from playing in this league. Some of these reflections are a bit high-level, but I think you’ll find them instructive or at least interesting.

WARNING: There will obviously be SPOILERS. If you haven’t finished the videos or haven’t watched them at all, I recommend you STOP and go do so before reading this post. Be sure to watch the games in order! The running time is equivalent to three “Godfather” trilogies(!), but I believe you’ll enjoy the journey. You’re also going to learn a lot.

Here’s Game 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5F-MWd7a87k

Here’s a Lichess study of my games: https://lichess.org/study/V4fidFKm

Lesson #1: Keep an open mind to maximize your results

In my Round 7 game vs. faznaz83 (2331), a rapid-fire opposite color bishop ending led to the following position after 57...Kd7.

I had just gone up two pawns and believed I ought to be winning. However, after Black’s king move I experienced a sinking feeling: Black’s plan is to send their king to the kingside to prevent the h-pawn from queening, after which they can sacrifice their bishop for the a-pawn and make a draw, as even with K+B+P vs. K I would have the famous “wrong color bishop” to help promote the pawn on h8. Jarred by this sudden realization, I played 58.a6?? with more than a minute-and-a-half remaining on my clock. Indeed, after 58...Bb8 Black’s king made a beeline to the corner, and we soon agreed a draw. Instead, 58.Ke4! would have gained a crucial tempo, e.g. 58...Bb8 59.Kf5 Ke7 60.Kg6+-, maneuvering my own king just in time to cut Black’s king off from sneaking into the corner via ...Ke7-f8-g7. White wins, as Black’s lone bishop would be unable to cope with the unimpeded advance of both the White h-pawn and a-pawn.

Why did I make this mistake? I had closed my mind to the possibility that I could still win. Sure, the win was a bit nuanced, and I was in moderate time pressure. But the biggest problem was that I no longer BELIEVED that the game could end in “1-0” instead of “½–½”. I hadn’t anticipated the difficulty of winning with two rook pawns (the sequence leading up to 57...Kd7 involved multiple pawn captures/pawn trades), and with 58.a6?? I was sort of throwing my hands up as if to say “Well, it doesn’t matter what I do now - I see Black’s idea, and it’s a draw.” This is a common mental mistake, and I should have known better. Always assume that any result is possible in a chess game. There is zero downside to this mentality! OK, if you have K+Q+R vs. K, obviously you know you can’t lose. But you could *certainly* still stalemate your opponent’s lone king. Maintain vigilance to the very end, and over time you’ll score extra half points and full points from positions where a less flexible player would have mentally capitulated, got careless in conversion, or even prematurely resigned. How many times has IM Eric Rosen pulled off his infamous Rosen Trap?

Lesson #2: Your mental dialogue is your anchor. Develop it!

A major benefit of doing live commentary of these LoneWolf games is that both the viewers and I have a largely unambiguous record of what I was thinking about on every move. Watching these 2-3 hour videos back has been EXTREMELY insightful in adjusting and tightening up my thought process. I feel like an athlete watching game film!

If you dig into some of these videos, you’ll notice that I tend to articulate my thoughts by asking and answering a series of questions:

- What was the point of my opponent’s last move?

- Before anything else, I try to identify what my opponent is up to. If I were my opponent, why would I have just played that move?

- What options should I consider in reply?

- I like immediately listing at least 1-2 possibilities. I still let my mind wander freely, but having a couple candidate moves gives me a useful roadmap for calculation and evaluation. Unless my reply is forced, this is almost always the most time-consuming stage.

- I’m ready to play a move. Is my move safe?

- Also known as a “blunder check.” I take a good look around to make sure I’m not missing anything, and only THEN do I execute my move.

The consistency and quality of your thought process determines your success in chess. The exact questions you ask yourself, the order you answer these queries, and their relevance to the position in front of you may vary. Sometimes there won’t be much to talk to yourself about, e.g. when you have a forced move or recapture. But I can’t emphasize enough how important it is to cultivate and follow *some form* of a mental dialogue that makes sense to you (if you’re unsure, I recommend trying the “Socratic method” style I describe). Doing so structures your thoughts, keeps you focused on solving the task in front of you, and cuts down on mistakes. Most chess players aren’t really thinking in organized fashion - they’re mostly reacting or bouncing around. We want to retain our process and equilibrium regardless of the calm or chaos of the position in front of us. You’ll eventually get to the point where this internal dialogue is as natural as breathing. By the way, when my opponent is on move, I’ll think more broadly about how the game may proceed, or I’ll use that time to crunch any new or existing lines that come to mind. I’ll also relax a bit more (naturally). You can be less rigorous when your opponent is the one on the clock.

Analyzing and annotating your games before looking at the engine is a powerful means of understanding your own mental dialogue. You might also consider recording *your own* commentary when you play! This could be especially helpful if you have no clue what your current mental dialogue looks like. Many chess players have never actually tried to articulate their decision-making process.

IMPORTANT NOTE: I’m not advocating some sort of “algorithm” or “system” to find the best move. This doesn’t exist, and anyone claiming good chess can always be inferred from “simple” or “easy” principles is a charlatan. I *AM* advocating a framework that gives us the best chance of understanding the position and producing consistently good decisions. Think of a basketball player about to shoot a free throw, or a golfer going through their pre-shot routine. That’s what we’re looking to understand and hone.

Lesson #3: If you’re dead set on one continuation, you probably ought to play it

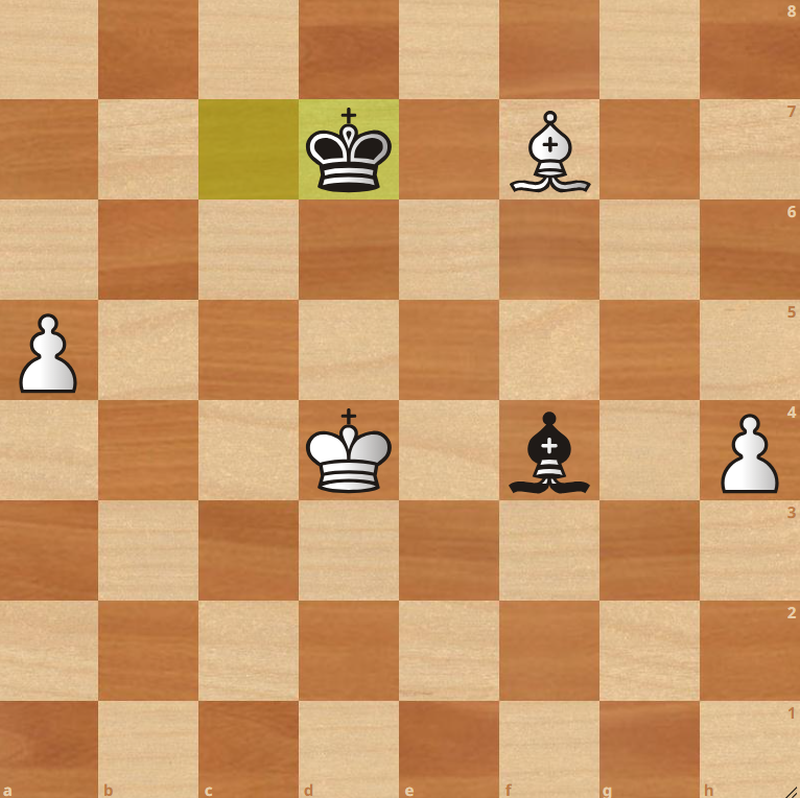

Here’s a position from my Round 10 game against FM Michael de Verdier, one of the other titled players in the field. My opponent had just played 18...a6, signaling a desire to break with ...b6-b5.

I had already decided that I would meet Black’s a-pawn push with the standard 19.a4 to prevent this idea, but then I got to thinking about the implications of 19...Nc6, offering a simplifying knight trade and loosening my grip on b5. I proceeded to hem and haw as to how I’d meet *that* move, but I never once seriously considered anything other than 19.a4. Finally, after spending 6 of my 16 precious remaining minutes, I played 19.a4 anyways, to which my opponent responded with 19...Nd7 - a move that wasn’t even on my radar!

This is a typical scenario for overthinkers: you spend a lot of time examining hypothetical lines for your opponent, but YOUR initial decision always remains the same. Don’t do this! You’re delegating too much effort to yourself rather than the player sitting across from you who actually has to decide upon a single reply. If you can’t improve on the move that’s dominating your calculation, it’s usually best to play it relatively quickly and offload the decision to your opponent. This is especially relevant advice in flexible positions (in sharp positions you have to be more careful). A surprising percentage of the time, your opponent will respond with a move that wasn’t even bothering you. I chatted with FM de Verdier after the game, and he said he hadn’t even spent much time looking at 19...Nc6.

The engine says he was right: 19...Nc6 20.Nc2! b5? 21.cxb5 axb5 22.b4! is strong for White, when Black has a hard time holding b5.

Lesson #4: The ideal player in 2025 has a diverse opening repertoire

My last classical tournament was in 2019. At the time, I was beginning to see the effect that powerful open-source engines and the proliferation of opening material were having on the opening phase. Strong players were better prepared than ever, and they were combing through your tournament games PLUS your online games to get a read on you (this reminds me: you might want to remove your name from your online chess profile!).

Participating in the LoneWolf League in 2025 has given me further confirmation of this trend, as I encountered many opponents and league participants who were very clearly booked up and using all their available resources to fight for an opening edge. See the video my Round 6 opponent, whenrooksfly (2176), made about his extensive Jobava London preparation for our encounter. You can also tell my Round 8 opponent, somerapidplayer (2280) meant business with the exotic-looking but engine-approved 7.b4!? Qb6 8.a4 they essayed against my favorite Scandinavian Defense.

For strong, serious players I think it’s more clear than ever: You need to have multiple openings in your arsenal. The game is too competitive and information too abundant these days to be a specialist - you’re an easy target if you stick to the same openings. It’s better to err on the side of being a generalist, capable of zig-zagging and playing multiple lines at any given time and forcing your opponents to go that much deeper if they hope to predict your tendencies.

If you’re 1800+ OTB and participating regularly in tournaments or leagues where you know your opponents are capable of preparing for you, I think you should be reasonably theoretically up to date and capable of playing one or two of the “big four” opening moves for White (1.e4, 1.d4, 2.c4, and 2. Nf3), plus two major defenses to both 1.e4 and 1.d4. For these Black defenses, it’s ideal if you have both a “solid” weapon and an “unbalanced” weapon, e.g. 1...e5 and the Sicilian Defense against 1.e4, and the Queen’s Gambit Declined and Grunfeld Defense against 1.d4. This might sound like a lot, and there is obviously nuance here, e.g. someone could be an exclusively 1.e4 player with either a narrow repertoire or a broad repertoire - it depends on how well they know and mix their subvariations. Mostly, you have to be honest with yourself: if you were preparing to play YOU, would it be easy or hard to anticipate what line would appear on the board?

As a semi-retired player who hasn’t seriously studied openings other than the Scandinavian Defense in recent years, I will readily admit that my opening diversity is subpar, and I think that was mostly borne out in these league games. It was a challenge to gain any sort of preparation edge in the 15-25 minutes I allocated to this task each game, and in a few games I definitely got outprepared, falling behind on the clock or winding up with a worse position. My strategy was mostly to get a measure of my opponent’s style and aim for flexible positions - especially with White. This worked reasonably well against the lower-rated cohort of players I faced (mostly in the 2000-2200 range), but players at my rating or higher would have punished me for foregoing objectively stronger lines. If I stage a serious chess comeback, broadening and strengthening my opening repertoire would be a top priority.

The good news is that most of you reading this probably don’t have to worry much about varying your openings. The vast majority of chess enthusiasts play online games against random opponents, so the chances that you’ll be outed for spamming the London every White game are low (a little dig against the London players out there, I’m sorry ;)). Also, if you’re an OTB player below 1800, I think you’re less likely to encounter opponents around your level who are capable of “punishing” you for a narrow opening repertoire - even with advance notice. Still, it’s worth thinking about developing multiple weapons to expand your opening horizons and your understanding of chess in general.

Lesson #5: You must never stop auditing your time management

Time management is underdiscussed because it doesn’t typically show up in the game score. It’s natural to look at a PGN or a game in a book and judge the moves we see in the abstract. But the reality is that the move quality in a timed game inevitably has a strong correlation to the time control and how the players manage that time allotment. The ticking clock is a tax on your decision-making: it’s inexorably eating away at the quality of your play!

Here again we can see the value of a real-time recording that captures every second that elapses. And boy did I feel those seconds (and minutes) slipping away! Despite the LoneWolf time control being 30 minutes with a 30 second increment (30+30), my clock frequently looked like this by the middlegame:

From my Round 5 game vs. Wilsonia (2244). A mere 4.5 minutes after 18 moves...I’ve already spent 85% of my time!

I need to work on my time management, and chances are you do too. Achieving consistent command of the clock is probably the most important “intangible” skill a competitive player can acquire.

Here is where I think I’m specifically managing my clock poorly and how I need to improve:

- I’m playing the opening too slowly. This is the most common phase where the minutes bleed out - you think “what’s an extra minute or two when I still have nearly all my time?” It adds up fast!

- More concretely, I’m spending too much time debating fairly equivalent decisions in the opening and early middlegame. I need to pick a line and get rolling.

- Often I’ll hesitate to play my sole candidate move (see the 19.a4 example vs. FM M-DeVerdier). I do this multiple times per game. It signals a lack of conviction, and it’s a habit I need to kick.

- Frequently I’ll decide on a move, proceed to explain it in detail, and finally play it. Instead, I ought to play the move and only *then* elaborate on it, if applicable. This is a unique challenge to live commentary, and I’ve never fully mastered it. Hikaru Nakamura is PHENOMENAL at this, by the way - despite being a prolific streamer who maintains a constant narrative when playing, he rarely gets in time pressure. He never seems to let his explanations get in the way of his move execution.

I’m pretty good at “playing on the increment,” (that is, relying on the perpetual 30 second bonus to save you), but as a player who experiences chronic time pressure you’re kinda forced to perform under pressure. It’s not ideal.

So, be ruthless in identifying the phases of the game and the types of decisions (or, more likely, non-decisions) where you're falling behind on the clock. Huge thinks are obvious culprits, but what’s holding you back may be a series of small bad habits that compound into many wasted minutes throughout a game. Give yourself some grace, though - time management is a never-ending process. I’ve been playing competitive chess for 25+ years and I’m still trying to figure it out!

Lesson #6: Long time control chess is the foundation for improvement

Though there are many productive means of working on chess, I believe regularly playing long time control games should be the core practice for an ambitious chess improver. You can get pretty decent playing blitz and rapid - especially if you’re young. But to realize your full potential, at some point you need to commit to serious online games (15+10 at minimum; preferably longer) and/or over the board tournaments. By making that leap, you’re demonstrating your openness to a level of chess where you and your opponents have sufficient time to investigate the opening, middlegame, and endgame, but not SO much time that the game is reduced to a scientific exercise (as in the case of correspondence chess). Classical chess is the perfect intersection between theory and practice, and it will push you to become the best version of yourself as a chess player.

I treated Season #37 of the LoneWolf league with the level of seriousness I would dedicate to an over the board competition:

- When pairings came out every Monday, I would message my opponent and offer a time or two during the week where I believed I wouldn’t be too stressed with work or life matters. I wanted to lock in a time where I could produce my best possible effort. For me, this ended up being mostly Friday and Saturday afternoons.

- I made a point to get ample sleep the night before my game each week. On game days, I cleared my schedule of commitments as much as possible.

- I ate enough beforehand that I’d feel satiated and fueled up for 2-3 hours of playing/recording, but not so much that I’d feel sluggish. Eating a heavy meal before a serious game is a mistake, in my opinion. Sometimes I’d walk for an hour or so before the game, or sit in the sun for 15-30 minutes.

- I adhered to a strict pre-game process: 15-25 minutes of prep; nothing beyond 30 minutes in order to avoid tiring myself out. I could have improved on this by preparing in the days leading up to the game, but I wanted to preserve the authenticity of the experience. I had my beverages (coffee, lemon+ginger tea, and water) ready to go when the game began.

- After each game, I conducted a thorough on-camera analysis. I made a point to make some observations and reflections BEFORE I looked at the engine. If I had not analyzed these games for YouTube, I would have analyzed/annotated them in a private Lichess study (a practice you DEFINITELY want to cultivate hand-in-hand with your serious games).

Would I have bothered with all this for a weekly competition? Of course not. That alone should indicate to you why long time control chess ought to be your primary vehicle for chess improvement. You’re going to take a weekly 30+30 game where pairings are known in advance and you spend 2-3 hours of your time MUCH more seriously than dozens of throwaway bullet/blitz games.

My diligence paid off, as I finished with 9/11 (+8, -1, =2) and took clear first place.

Granted, I was the top seed. But this league was by no means a cakewalk, and I had little margin for error after a Round 4 loss to happy_mode (2308). I was extremely impressed by the level of competition I faced in the Open section of this league. None of my games were easy! As you can see, I believe I still have a lot to work on.

Most importantly, I came away with a strong sense of personal accomplishment in battling it out on camera for 11 straight weeks, and a renewed appreciation for the beauty and depth of chess. This experience solidified my belief that participating in long time control chess is key to not only chess improvement, but a fulfilling chess experience overall. Entering even just one serious tournament in your life - be it online or in-person - may be the most formative chess memory you’ll ever have. If you take a single thing away from this post, I hope it’s a push to PLAY LONGER GAMES!

Concluding thoughts

I will definitely be playing a future season of the LoneWolf league (perhaps Season #39), and I would recommend LoneWolf or the 45+45 league to anyone who wants to dip their toes into serious chess. Players of all levels participate, and the LoneWolf league has both an Open and a U1800 section. It was heartwarming to see how many viewers decided to join one or both of these leagues after watching my YouTube videos! The leagues are completely free, run continuously throughout the year (with small breaks), and accommodate players with busy schedules by allowing for multiple byes and even latejoining. Everything is run through a Slack channel, and there’s a real sense of camaraderie amongst league participants (along with quite a few characters!). It’s common to see league participants watching and supporting their friends and fellow competitors. Shout-out to my opponents (all of whom were extremely friendly), league participants, and moderators.

Registration for LoneWolf Season #38 is currently OPEN.

You may also like

ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_StatsWhere do Grandmasters play Chess? - Lichess vs. Chess.com

This is the first large-scale analysis of Grandmaster activity across Chess.com and Lichess from 200… CM HGabor

CM HGabor